Europe is no longer the sick man of the world economy.

The 19-nation euro-zone bloc is already enjoying the strongest growth in a decade and now economists at Credit Suisse Group AG and Oxford Economics are declaring that it’s heading toward a golden period of low-inflationary expansion.

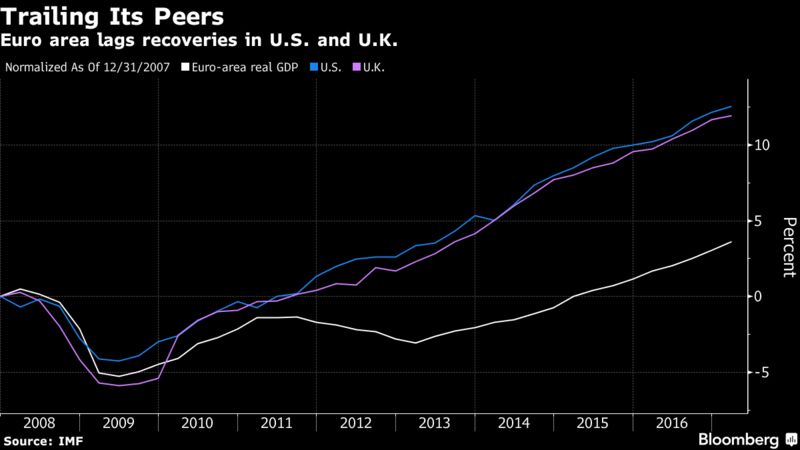

The turnaround is striking for a region that plunged from the global financial crisis into its own sovereign debt turmoil, record unemployment and near-deflation that threatened the very survival of the currency union. While still to make up most of the ground lost in the dark years, and with productivity still weak, the upturn at least holds out the hope that some scars will start to heal.

The improvement has plenty of room to run, says Angel Talavera, an economist at Oxford Economics in London. The European Commission last week raised its 2017 growth forecast to 2.2 percent from a 1.7 percent estimate in May.

Economists surveyed by Bloomberg have raised their growth forecasts eight times this year. Data due Tuesday is predicted to show the region gained more momentum in the third quarter by expanding 0.6 percent, faster than the long-term trend, according to Bloomberg Economics.

“More than four years into the current expansion, most indicators signal the euro-zone economy is still somewhere around mid-cycle,” Talavera said.

“Absent an unexpected shock, we should see several more years of economic growth.”European Central Bank policy maker Benoit Coeure last week went as far as to say that in terms of balance and robustness, the economy is in the best shape since the euro’s birth in 1999 although he called on governments to implement more reforms to support it.

Propped Up

The virtuous cycle is being mainly underwritten by the ECB, which fended off the debt crisis and locked in ultra-loose monetary policy, and executed by the continent’s companies and households. Corporate profits are beating estimates and consumer confidence is at the highest since 2001.

The bright prospects for the euro region paint a stark contrast to the outlook for the U.K., where the uncertainty surrounding the imminent divorce from the European Union is crimping investment and weakening the pound. The spread between 10-year and two-year government bonds has shrunk to about 80 basis points this year in Britain, while it has swelled to more than 110 basis points in Germany, indicating a greater level of confidence in the biggest European economy.

Still, the recent wounds run deep in the euro area. Productivity growth is nowhere near levels recorded at the start of the millennium, a quarter of young people can’t find a job and unemployment in the region’s periphery still exceeds 10 percent. And even at its current pace, growth will probably still lag behind the U.S. Inflation of 1.4 percent in September remains below the ECB’s target of just below 2 percent.

Support for the single currency — although on the rise — has yet to reach its 2007 high and euroskeptic political parties have gained ground. The anti-euro AfD party became the third largest in the German lower house after elections in September. The populist Five Star Movement in Italy is strengthening before next year’s general election.

Other political earthquakes, such as Catalonia’s bid for independence from Spain, have the potential to cause further ruptures. As ECB President Mario Draghi has noted, international geopolitical shocks are a key source of risk.

To insulate the economy, the ECB announced in October that it will continue to buy public and private-sector debt for most of next year and won’t raise interest rates for a long time thereafter, guaranteeing an expansionary monetary policy.

With few signs yet of accelerating price growth, Nordea Bank said last Wednesday that it doesn’t expect any rate increases until December 2019, after Draghi has finished his term.

Capacity utilization is close to historic cyclical highs, which bodes well for investment and jobs. Rising employment in turn should bolster private consumption, while exports are set to benefit from robust global trade.

“All the new indicators that have come mostly so far of the so-called soft nature indicate that growth could be indeed stronger and that would not surprise me,” ECB Vice President Vitor Constancio said last week.

Even fiscal policy might contribute. Germany, the region’s proponent of austerity, is looking at tax cuts for Chancellor Angela Merkel’s fourth term in office. Goldman Sachs Group Inc. economists estimate that the area-wide budget position will ease next year.

“There’s good cause to think euro-area growth can gather further strength in 2018,”’ said economists at Credit Suisse, who last week raised their forecast to show a 2.5 percent expansion next year. “And risks are to the upside.”

Bloomberg